Older even than the dinosaurs, a fossil found in Barraba after the big flood of 1964 has been found to be from one of the earliest plants on Earth.

The fossilised plant is older than mammals and older than flowering plants. Fresh examination of this Barraba fossil has revealed evidence of a new plant species that existed in Australia more than 359 Million years ago.

This is considered an extraordinary discovery. Antoine Champreux, a PhD student in the Global Ecology Lab at Flinders University, has catalogued the discovery of the new fern-like plant species as part of an international effort to examine the Australian fossil in greater detail.

The fossil was found in the 1960s by amateur geologist Mr John Irving, on the bank of the Manilla River in Barraba, New South Wales. The fossil was exposed after major flooding events in 1964, and Mr Irving gave the fossil to the geological survey of New South Wales, where it remained for more than 50 years without being studied.

It was dated from the end of the Late Devonian period, approximately 372- to-359 million years ago – a time when Australia was part of the Southern hemisphere super-continent Gondwana. Plants and animals had just started to colonise continents, and the first trees appeared.Yet while diverse fish species were in the oceans, continents had no flowering plants, no mammals, no dinosaurs, and the first plants had just acquired proper leaves and the earliest types of seeds.

Well-preserved fossils from this era are rare ñ elevating the significance of the Barraba plant fossil. The fossil is currently in France, where Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud, an international expert studying the first plants on Earth, leads a team at the French Modelling of Plant Architecture and Vegetation (AMAP) in Montpellier.

This French laboratory is particularly interested in further examination of Australian fossils from the Devonian- Carboniferous geological period, to build a more detailed understanding of plant?evolution during this era. Mr Champreux studied the fern-like fossil during his masterís degree internship at AMAP and completed writing his research paper during his current PhD studies at Flinders University.

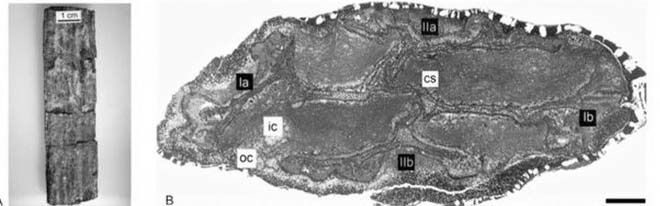

“It’s nothing much to look at – just a fossilised stick – but it was far more interesting once we cut it and had a look inside,” says Mr Champreux. “The anatomy is preserved, meaning that we can still observe the walls of million- year-old cells. We compared the plant with other plants from the same period based on its anatomy only, which provides a lot of information.”

Mr Champreux found that this plant represents a new species, and even a new genus of plant, sharing some similarities with modern ferns and horsetails. ìIt is an extraordinary discovery, since such exquisitely-preserved fossils from this period are extremely rare,” he says. “We named the genus Keraphyton (like the horn plant in Greek),and the species Keraphyton mawsoniae, in honour of our partner Professor Ruth Mawson, a distinguished Australian palaeontologist who died in 2019.